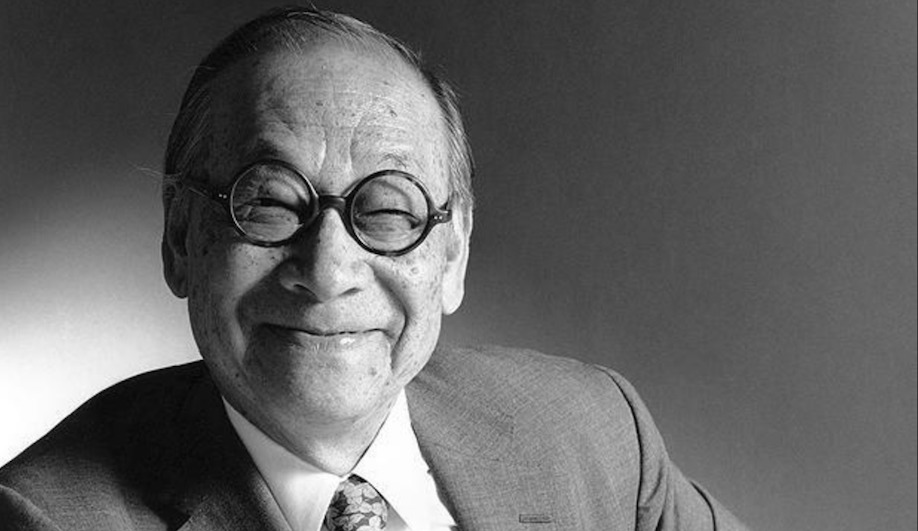

The American industrial designer who literally wrote the book on ergonomic design died on Saturday at the age of 84.

A designer who put functionality above styling, Diffrient is best known for the task chairs he created – Freedom, Liberty and the Diffrient World chair – for Humanscale. From the first one – released in 2000 – onward, he eschewed the levers, cranks and other clunky mechanisms of task chairs for a chassis that automatically adjusted to the user’s height and weight, allowing him or her to easily shift positions.

Diffrient was born in Star, Mississippi, in 1928, and grew up in the South and in Detroit, where his father moved the family to take up work in the car industry. In a TED talk he gave in 2009, Diffrient described how his early love for airplanes – and the romance of flying – sparked his passion for design, which he pursued after studying aeronautical engineering. The trajectory from airplanes to chairs was intuitive: “Instead of a product shaped by the wind, it was shaped by the human body,” he noted.

While at the Cranbrook College of Art and Design, Diffrient worked for Eero Saarinen, with whom he designed the Knoll Saarinen 71 chair in 1950. After landing a Fulbright scholarship, Diffrient flew to Milan, just as the city was experiencing its renaissance as a design mecca, and worked for Marco Zanuso; together, they designed the Compasso d’Oro–winning Borletti sewing machine.

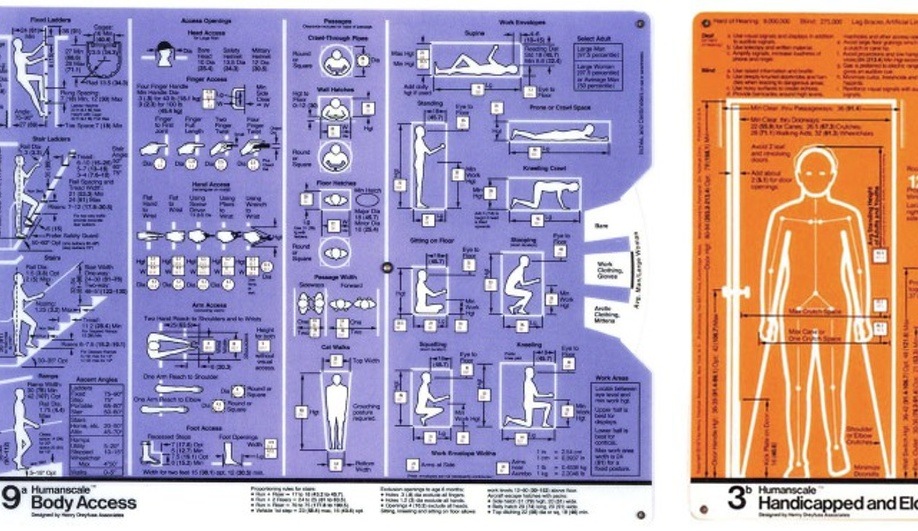

In 1955, he returned to the U.S. to work for Henry Dreyfuss Associates. While there, Diffrient got to design for airline companies – he led on American Airlines’ livery design, as well as its concept for a lightning-fast plane to rival the Concorde. But more important was the company’s research into ergonomics, which fed into Humanscale, the seminal three-volume reference book Diffrient co-authored in 1974 and 1981. It provided science-based illustrations and data that covered the full spectrum of body types, positions, behaviours and abilities. Informed by these “human factors,” designers could create products, furniture and spaces that are accessible to the greatest number of people.

Yet, after 25 years at Dreyfuss, Diffrient felt tapped – “I was putting out romance, and not getting anything back” – and started his own studio.

His first major product would come out in 2000. The Freedom chair featured an automatically tilting back, arm rests that easily moved out of the way, and a head rest that self-adjusts as you lie back. Designed for Humanscale – a manufacturer founded on the same ergonomic principles Diffrient set out in his book – it responded to a range of body types, from a slim five-foot woman to a broad-shouldered 6.6-foot man.

He followed Freedom up with Liberty, an even more minimal chair with a flexible mesh back; then the Diffrient World chair, which went all mesh and was completely mechanism free. Each iteration represented several years of hard work.

In his TED talk, Diffrient describes his process as designing for what the body needs and wants rather than starting with a preconceived notion or a style. Beginning with a set of loose ideas based on how people work in an office, he created chairs that, as he remarked, do as much as mechanistically possible without the user having to fuss with them. By stripping away as much as possible, his designs also happened to be environmentally sustainable. For his innovations, he was awarded in 2002 with the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Award for Product Design.

“Niels believed in the importance of function and knew that great design must be driven by function,” says Bob King, Humanscale’s founder and CEO. “This is why his products often transcend any specific time or place. What he believed in is so evident in his work that his legacy will live on through his designs. On a personal note, some of the most joyful times in my life were those we spent together. He was a great friend and he will be missed.”

Though he was well into his eighties, Diffrient showed no signs of slowing down. In 2012, he published Confessions of a Generalist, which recalls his experiences in design through words and pictures. As recently as April, he was working on new products in his Connecticut home and studio, which he shared with his wife, tapestry designer Helena Hernmarck.

With the same mix of pragmatism and passion that guided his work, he told Azure’s Nelda Rodger in 2010 how he was still doing it all after 50 years. “It’s a compulsion; I can’t really stop. But I work in postures that don’t overstress me, and I refuse to work at a computer. I have younger people do my computer work. And there’s one thing that’s perfectly obvious that most people ignore: diet.”