It’s become more and more difficult to tell the difference between a rendering and a photo. But is that problematic for architectural photography? Nicholas Hune-Brown explores.

One day in the fall of 2015, the architecture critic Blair Kamin was reviewing the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects’ annual design awards when he stopped short. That year, the jury had awarded honours to diverse projects from across the world – a soaring office tower in Shenzhen and a corporate headquarters in Munich, a natural history museum in Shanghai and a high-concept office called Spacecraft in Spain. As Kamin scrolled through the names, however, it was a local building that caught his eye.

El Centro is a satellite of Northeastern Illinois University, built along the Kennedy Expressway in Chicago – a striking structure that the awards jury had praised for its “sculptural form and vibrant facade.” It was a building Kamin knew well. He had reviewed it positively a year earlier, noting its “exuberant shape and bright colours.” But it was also a building that he believed had a major flaw: the gray row of enormous air-handling units that had been plunked on the roof, seemingly unaccounted for by the architect.

The grey air-handling units on top of El Centro’s roof. Image: Chicago Tribune

The critic was curious: how had an awards program overlooked the unsightly units? When he looked at the photos that had been submitted to the jury, he quickly found the answer. In the images, the giant gray boxes had been completely removed. With an assist from Photoshop, the view of El Centro’s profile from the highway was now as razor-sharp as it would have been in the architect’s mind – an idealized vision of a building presented to jury members who would never actually visit the site.

The edited version of El Centro with the HVAC units removed. Image: Chicago Tribune

Kamin is a Pulitzer-prize winning critic. He’s spent decades looking at photos of buildings – first as black-and-white glossies that would arrive by mail, now as digital images that appear in his Dropbox. He knows that the images he sees have been cleaned up to present a building at its best, removing an unsightly electrical wire or street sign. But the El Centro changes seemed to go a step too far. “There’s a difference between editing the surroundings of the building and editing the building itself,” says Kamin. “Once you start editing the building itself you’ve really crossed the line into a different reality.”

Kamin’s Chicago Tribune column, “Doctored photo raises questions about ethics in architecture contests,” immediately caused a stir. “Oh my god, people were thrilled,” he says.

Architects were thrilled. Because someone had finally called out an architect and a photographer for this process of faking it.”

But while some in the industry may have been delighted, the El Centro images were hardly rogue outliers in the world of architectural photography; they were simply the shots that happened to catch one critic’s eye.

Commercial architectural photography has always been about presenting an idealized version of a building; photo-editing software has merely expanded the horizons of what is possible. And in an industry in which everyone – from architects to photographers to click-hungry blogs and magazines like this one – has an interest in producing the “wow” image, the line between touching something up and altering it entirely has become murky.

The El Centro controversy came at a moment in which the relationship between photography and architecture has become more complicated than ever. Each day, on blogs and on Instagram, the public is treated to an endless parade of perfect images — remote houses glowing at dusk, deserted museums looming at impossible angles. In an age in which more people will see the idealized photograph of a project than ever visit the physical building, this steady stream of pictures threatens to invert the relationship between architecture and photography.

“We are living in a digital age, and architecture itself has become a virtual commodity,” says the curator and architecture writer Elias Redstone, whose book on the topic, Shooting Space: Architecture in Contemporary Photography was published by Phaidon in 2014. If the world is consuming architecture online, through a series of increasingly unbelievable images, why build anything at all?

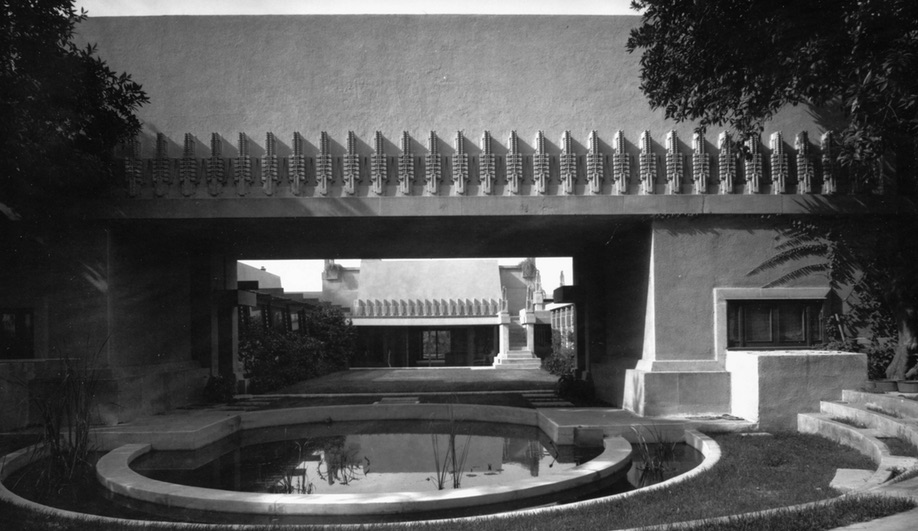

Hollyhock House in West Hollywood, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1919-1921). Image: Julius Shulman

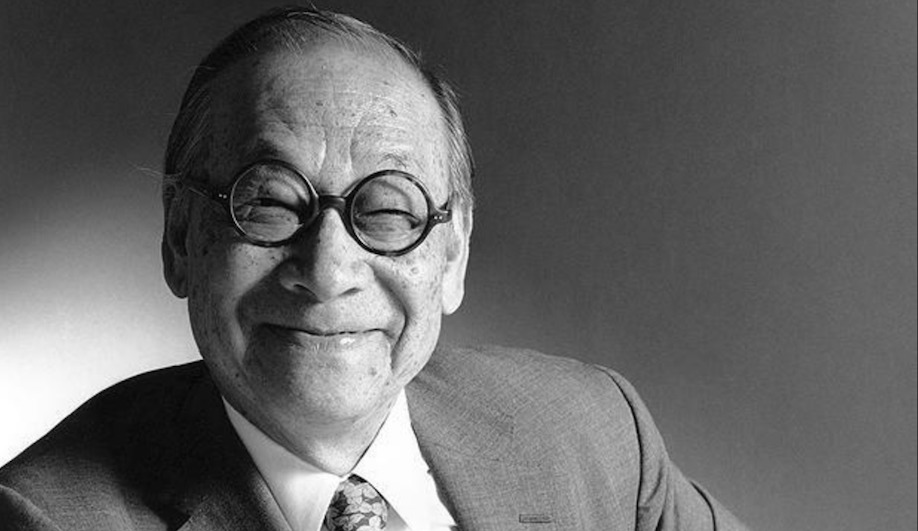

Photography and architecture have always had an intimate relationship. With their patient solidity, buildings were the ideal subjects for the long-exposure times of early cameras. And while painters and other artists had conflicted feelings about allowing the camera to reproduce their work, architects largely embraced the photograph, quick to see the advantages of a medium that could translate their three-dimensional creations into easy-to-digest forms and disseminate them across the world.

After the Second World War, commercial photographers like Julius Shulman and Ezra Stoller not only captured the great architects of their time, but helped create an idealized vision of mid-century modernism itself. To “Stollerize” a building was to turn an agglomeration of glass and steel into something intensely desirable. With his beautifully lit, carefully composed shots of modern California life, Shulman was as much marketer as documentarian.

“I sell architecture better and more directly and more vividly than the architect does,” he once said.

AA Robins Architects’ Point Grey Road Cube House, Vancouver. Image: Ema Peter

For Ema Peter, a Vancouver-based photographer whose work has been published in Azure, as well as Dwell and the New York Times, the aim isn’t to sell architecture so much as to present it in its purest form. The Bulgarian-born photographer sees herself as an advocate and an interpreter, someone who is passionate and fiercely protective guardian of the architect’s vision. “I will photoshop so much out of a building until the vision is there,” says Peter.

Recently, she shot a building with a prominent metal overhang that was supposed to feature a series of parallel lines. The builders, however, had down a shoddy job. “There wasn’t a straight line,” says Peter. “So we straightened them.” A corner that’s finished badly, an unfortunate door, unwanted air vents — all can be removed with a few clicks of the mouse.

If the builders screwed up or the budget got cut in half when you’ve done this spectacular vision of a building, why should you be punished?”

“Why can’t you just Photoshop whatever you want to make the building look like whatever your vision was?” asks Peter.

Peter knows her stance is controversial. “People believe that there should be almost no post-production and the buildings should be displayed the way they are,” she says. “But I stand my ground with this.” Peter is a true believer, someone who sees in modernist architecture “a glimpse of what the future looks like.” For her, a photograph is not documentary evidence of a building’s reality, but a way to protect an architect’s vision against the ravages of subpar contractors and cheap clients.

James K.M. Cheng Architects’ Elm Street Residence, Vancouver. Image: Ema Peter

While Peter is unapologetic about her belief in the need for post-production, other photographers are more circumspect. Nic Lehoux is a veteran who began his career shooting 4×5 film, carefully setting up each shot with the knowledge that every click of the shutter cost $10. “You’ve opened up a Pandora’s box when you can take an infinite number of images,” says Lehoux. “You can go in and tweak the colour. You can moderate that somewhat. Speaking for myself, I don’t do that. I’m very much an in-camera guy.”

U.K. Pavilion at Shanghai Expo 2010, by Thomas Heatherwick. Image: Nic Lehoux

But Lehoux has no compunction when it comes to removing unsightly exit signs and sockets.

“I don’t consider removing switches and fire alarms cheating,” he says. “The architects don’t have control over the necessities of signage. In a sense they’re the victims of whatever the code has to be.”

The architects who commission these photographs have conflicted feelings about post-production. Chinese architect Ma Yansong says that when he commissions a photograph, he wants the artist to offer his or her own interpretation. “Strong architecture doesn’t require a lot of editing. The building and space should speak for itself,” he says. At the same time, he wants photos to show a building at its best. “I understand the need to shoot the beautiful side of a building,” says Ma. “It’s like when you summarize a good novel or movie—you want to talk about the technical effects, the positive aspects and what makes it great.”

Musee National des Beaux Arts du Quebec by OMA, Quebec City. Image: Nic Lehoux

For Omar Gandhi, the question of how far to take post-production work is one that gnaws at him. “It really is something I think about,” says Gandhi. “And it’s something I sometimes feel a little sad about.” The 38-year-old architect has had remarkable success in his short career, with images of his private homes in rural Nova Scotia featured in magazines and online. For Gandhi, the most exciting shots are the ones that highlight a particular mood or tell a story, positioning his buildings in the midst of a wild, often harsh landscape.

Omar Gandhi’s Lookout at Broad Cove Marsh, Nova Scotia. Image: Doublespace Photography

As in the world of fashion photography, however, the simple truth is that the public has become accustomed to a certain perfection in their images. If every other photo of a building online and in magazines is pristine and perfect, it’s difficult to be the one person offering a crooked line and an unsightly exit sign. And the right photograph can bring his work to an audience that will never visit the foggy wilds of the Maritimes.

“In our own work I think we’re fairly disciplined about it and try to show some of those imperfections,” says Gandhi. “But the truth is that there could probably be more imperfections and that would be a more honest representation.” Gandhi worries that the kind of perfect photos that he sees online aren’t just unethical — they give the public an unrealistic vision of what architecture is.

“I see it as a very dangerous thing. It’s such a different thing than architecture. I just hope that people don’t lose that love for experiencing buildings.”

Float House in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by architect Omar Gandhi. Image: Doublespace Photography

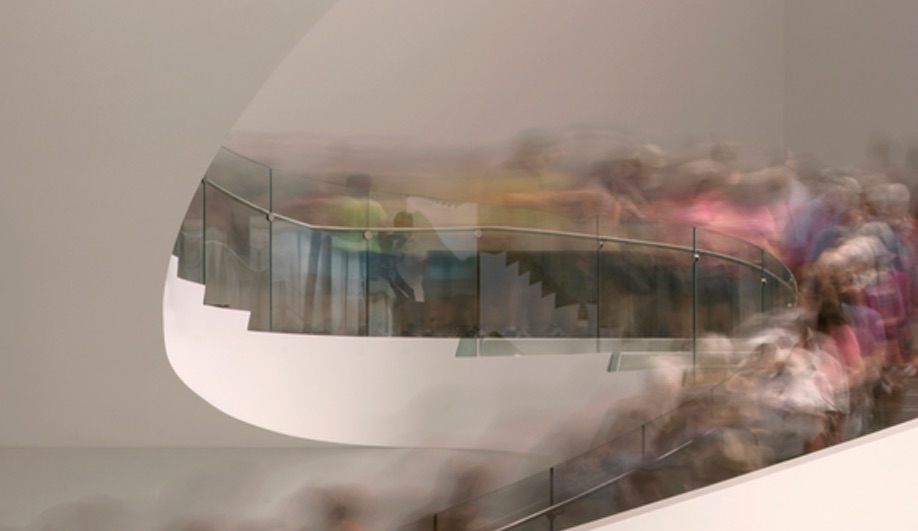

A few years ago, Elias Redstone became frustrated with the images of buildings he was seeing online. “It was a moment when we were being overwhelmed with imagery of architecture and all these blogs had started up and the internet had taken over,” the curator remembers. “And the photographs that we were being bombarded with on a daily basis were increasingly generic and anodyne and kind of empty.” The images that Redstone was seeing weren’t just boring, they seemed to represent an existential threat to architecture. As renderings became more photorealistic and photographs became more like renderings, any space for engaging with the building itself seemed to shrink.

Today, Redstone says, he’s seeing improvement. “Architects are beginning to understand that the generic blue sky doesn’t make their work stand out, but actually makes their work disappear in the constant stream of imagery,” he says. Redstone is seeing more people in photographs. The magic-hour shot has become a cliché. In-demand photographers like Iwan Baan have put buildings in their social context — capturing a Chinese worker toiling before the shining Shenzhen Stock exchange or using a helicopter to take an aerial shot of Ma’s Chaoyang Park Plaza in Beijing just as a flock of birds swoop by its mountainous form.

Chaoyang Park Plaza by MAD Architects, Beijing. Image: Hufton+Crow

Blair Kamin agrees: “It’s much more journalistic in spirit … We’re not just seeing buildings from the architect’s perspective, as their platonic ideal, but in a way that approximates reality.”

This doesn’t mean, of course, that photographs are necessarily more “truthful”—just that we value a slightly more imperfect aesthetic. The fact is that for as long as photographs are the primary way we interact with architecture, there will always be a disjuncture between the image on our screen and the building on the ground. For the architect Daniel Libeskind, the digital age has only accentuated this inherent tension. When Libeskind looks at photos of his own work, he almost always hates them.

“I just don’t trust any photograph,” he says. “Often people form a sense of the architecture from a photograph. Then you go around it and say, that’s totally different. It’s fraudulent. The photograph was just a fake image, just one point of view.

It’s an ideology that’s being presented, not the actual building.”

What Libeskind is talking about isn’t the fakery of Photoshop, but the falseness inherent to photography itself, a medium that can take a space and turn it into a two-dimensional icon. “Photography has helped architecture in the sense that it has made buildings look better than they really are,” says Libeskind. But while a striking image may be a brilliant way to market a project, it also fundamentally cannot capture the experience of visiting a building.

Libeskind Studio’s Sapphire residential building in Berlin. Image: Jan Bitter

When Libeskind thinks about his architectural ideals, he thinks about how it feels to walk into a Gothic cathedral. To enter through the stone portal and feel the way the vaulted ceiling opens up, pointed arches soaring towards heaven, is to experience the very essence of architecture. And it is utterly unphotographable. No number of dramatically lit shots can reproduce the structure’s aura, the feeling of having the building unfold before you as your steps echo across stones laid 800 years ago. The point of architecture, for Libeskind, is to create something that escapes photography. The most an image can do is try to capture a sliver of that feeling.

Have architectural photos become too stylized? E-mail your thoughts to feedback [at] azureonline [dot] com.

This story was taken from the March/April 2017 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.