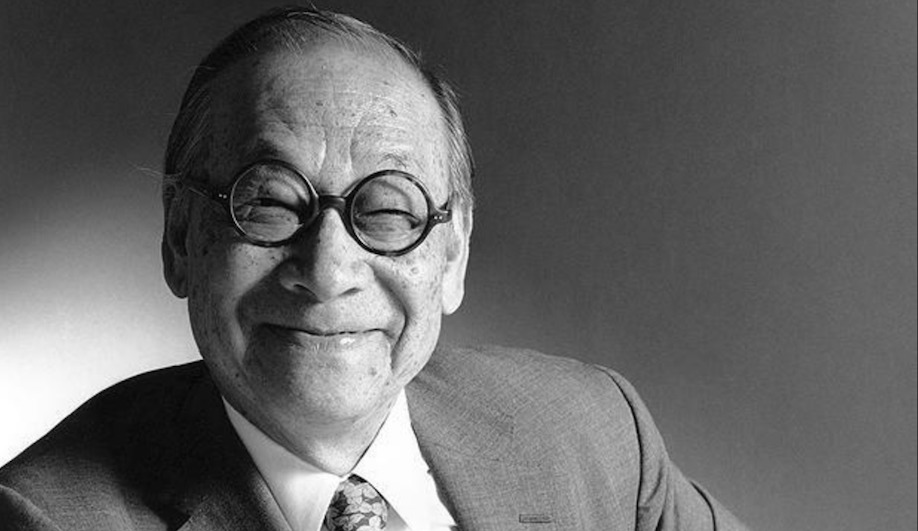

Renowned for his imaginative solutions to emergency shelters and low-tech architecture, the “paper” architect has been awarded the industry’s most prestigious award.

Last night, Shigeru Ban became the recipient of the 2014 Pritzker Architecture Prize. He is the sixth Japanese architect to receive the award.

Now 56, Ban is unique in his field. He designs elegant, innovative work for private clients and high-end developers, and uses the same inventive and resourceful design approach for his extensive humanitarian efforts.

A large part of his career has gone into travelling to places ravaged by natural and man-made disasters, and finding cost-effective solutions for building relief shelters and temporary public buildings. His ingenious solutions are often the first steps toward a community’s healing process.

Among his best-known efforts is the Cardboard Cathedral in Christchurch, New Zealand, built pro bono after an earthquake in 2011 destroyed one of the city’s Anglican churches. Ban’s A-frame building, made from cardboard tubes and coated with waterproof polyurethane and flame retardants, rises 78 feet and can seat 700 people.

Ban also responded quickly to the Tohoku earthquake crisis in Japan in the same year, by devising temporary privacy walls in gymnasiums. The public school facilities had become shelters for thousands of families who lost their homes. A simple kit of parts, the cardboard partitions gave the displaced victims a sense of privacy and dignity while sharing space with neighbours, in some cases for months at a time.

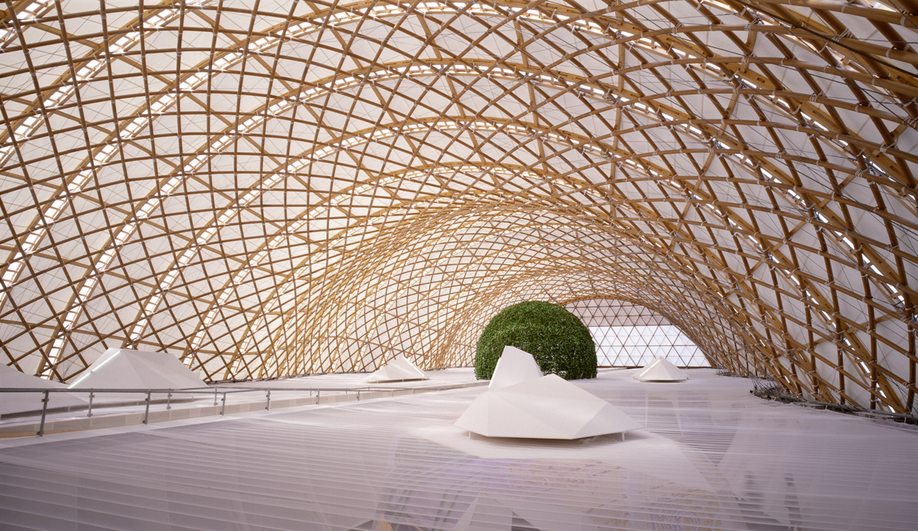

Another one of Ban’s most remarkable achievements is finding ways to reinvent ancient construction techniques. Centre Pompidou-Metz, completed in 2010, is topped with an undulating fibreglass canopy pierced by flagpole towers. Its pitched form consists of glued laminated timber that dramatically intersects to form hexagonal units that resemble the cane-work in traditional Chinese sun hats.

For the Tamedia headquarters in Zurich, Ban built a seven-storey timber building using miyadaiku and sukiya-daiku, two Japanese carpentry methods traditionally applied to teahouses and temples. The joinery – dog-bone shaped beams that insert into one another and lock into place – require no nails, screws or other hardware.

In 2008, Rachel Pulfer interviewed Ban for Azure while he was working on the Pompidou-Metz out of a temporary office made of paper he installed on the rooftop of the original Pompidou, in Paris. Ban described his thoughts on how his diverse creative streams feed one another:

“For me, there is no difference between permanent and temporary structures. Some of the paper houses I made for victims of the earthquake in India became permanent because many of those people didn’t have houses to begin with. After they went back to the village, they dismantled my houses and rebuilt them, so they became permanent. When I work with developers, they sometimes destroy the building, so it becomes temporary. Whether a building is temporary or permanent depends on whether people love that building or not.”

The Pritzker Prize ceremony will be held June 13, 2014, at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.