For decades, Poland has been a hub for high-end furniture manufacturing. Now it is emerging as a hotbed for creative talent. Here’s an exploration of contemporary Polish design culture – and why it’s rising locally and globally.

Last winter, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute (IAM) invited a group of international journalists to Poland. The organization, which is supported by the country’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, arranged a flurry of activity – studio visits, walking tours, foodie experiences – all centred around a pinnacle event: the opening of the Gallery of Polish Design at the National Museum of Warsaw. At the ribbon cutting, the guests of honour were so many that their chaotic attempt at a group photo bottlenecked the central stair. The museum was brimming with local cultural figures and designers, from the legendary social realists to the millennial internationalists, whose works were finally being given a permanent spotlight. The exhibition in the first-floor gallery spanned from the folk-heavy, turn-of-the-century Zakopane era to the modernist present.

The trip was an eye-opener. Poland is taking an active role in broadcasting its design culture, or rather its design as culture, to the world. While the country has many advantages – namely its manufacturing base, geographical location and (now precarious) E.U. status – it has also made decisive moves that could be instructive for any country (or city) with a perpetually emerging design scene. In 2013, the IAM officially brought design under its auspices and promoted it along with Polish cinema and art. The institute has since published design books and spearheaded such programs as Let’s Exhibit!, which supports solo designer shows at international fairs. It also runs the vibrant web portal culture.pl. Government granting programs have further incentivized the industry, and the combined influence of these factors has led to made-in-Poland brands gaining recognition around the globe.

It’s an impressive synergy of government and industry. Just as a comparison, in Canada, it’s only been since 2017 that the federal Creative Canada strategy has mentioned design alongside other creative industries. In Ontario, there are no policies focused on design, even though Toronto alone boasts 17,300 industrial designers, the third highest tally in North America after New York and Boston.

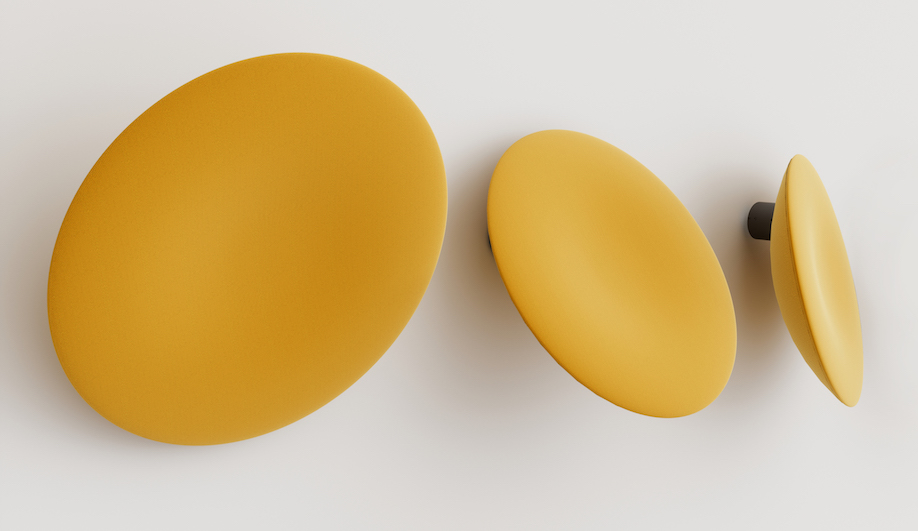

Oscar Zieta, one of Poland’s best-known exports, uses FIDU technology as his main method. Two ultra-thin sheets of steel are welded together and inflated under high pressure. These Tafla mirrors were launched at IMM Cologne in January.

Poland’s recent government-led push has helped increase awareness globally. But the design community has also stepped up to the plate. Just a decade ago, Oskar Zieta and Tomek Rygalik were the only big names on the international stage. Today, they’re joined by dozens of talents showing at prestigious fairs. Malafor’s inflated-cushion seating has appeared at Fuorisalone; Bartek Mejor’s digitally sculpted porcelain lighting for Fabbian at Euroluce; and Tartaruga’s pop-arty kilims at the London Design Festival. Expats are also representing: London-based Marcin Rusak won the Rising Talent Award at Maison et Objet in Paris last year for his baroque Flora collection, while Aleksandra Gaca is the go-to for futuristic 3D textiles. Inside Poland, the Łódź, Gdynia and Kraków design festivals are showcases for reimagining the future of food and cities in experiential exhibits.

And design education has been galvanized. The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and the School of Form in Poznań (the latter having opened in 2011 under the direction of leading trend forecaster Li Edelkoort) give students real-world experience working directly with industrial partners. Warsaw even has a city architect, Marlena Happach, who is mandated to create a strategic plan for the next 20 years. Her office has already launched an international competition for a pedestrian and bicycle bridge through the Vistula River. “Good design is the citizens’ right,” she told me.

Design and designers are thriving more than in the past. A 2015 report by the Institute of Industrial Design found that 40 per cent of the designers interviewed were able to successfully sustain a living. “That percentage is high,” says IAM director Krzysztof Olendzki. Referring to the many ways Poland is positioning itself in design, he says, “From outside, this process can be perceived as rebranding. Actually, it is a way to popularize knowledge [of] the trends that have existed here for a long time.” The big difference now, he says, is that Polish manufacturing is no longer the domain of anonymous production.

The Ume chair for the Polish brand Comforty. Its designer, Maja Ganszyniec, is based in Warsaw and works with such international companies as Camper and Ikea.

This is Poland’s best-kept secret: The country is the fourth largest furniture manufacturer in the world. From communist times until recently, the nation’s subcontractor-producers have made quality furniture for Western brands, with products for Fritz Hansen, Hay and Tesco among the country’s biggest design exports.

Young designers are now tapping into this industrial know-how, and the companies themselves, including Comforty and Paged, are launching collections under their own brand names. One of Comforty’s most impressive pieces is the Ume chair, its roundness wrapped in a kimono-like upholstery, by Maja Ganszyniec. At 36, Ganszyniec is in the prime of her career, yet old enough to remember the early 1990s and communism. When she returned to Warsaw after studying at London’s Royal College of Art and working for the Italian legend Alessandro Mendini, she says the city was a desert. “We didn’t have any brands. I’m part of the first generation to run my own studio.” She’s also creating furnishings for Ikea and for its higher-end PS collection.

Timing is everything, and Poland’s design moment is colliding with other, alarming developments. Since the election of the populist Law and Justice (PiS) party in 2015, the country has slid inexorably to the right; the three-year-old administration has taken an anti-refugee stance, intervened in the judicial system, infringed on women’s rights and censored speech. It has also swapped out the leaders of many cultural institutions with more amenable allies. For many designers, this turn of events reverberates with cognitive dissonance.

“It’s confusing what’s happening here,” said Agnieszka Jacobson-Cielecka, program and artistic director at the School of Form. “We all trust it’s going to stop – that it’s a mistake of four years – before they can destroy too many things.” But then she expressed another commonly voiced sentiment: “Polish culture is never as good as it is in times of oppression – in some ways it’s what stimulates people.” A perfect example is Luka Rayski’s protest poster design for Democracy Illustrated. Featuring the word KONSTYTUCJA (constitution), printed in black, with the TY (meaning “you”) and the JA (“me”) emphasized in white and red, the graphic is now an icon of mass appeal.

Then there’s the School of Form, which pushes the pedagogical parameters of education while actively connecting students with industry. The school was founded by Piotr Voelkel, whose family owns Vox, a furniture manufacturer that boasts 120 shops and 350 stores-within-a-store in Europe. In an act of enlightened industriousness, the brand started the school to create a pipeline to new design talent. At the same time, the company was wholeheartedly investing in a novel platform focused on the anthropological, sociological and philosophical approach to design education that Dutch maven Li Edelkoort originated at Design Academy Eindhoven. (A founding director of School of Form, Edelkoort remains as a mentor.)

The school is now working toward establishing an architecture department that offers a broader perspective than what students get at technical universities. “We’re asking, ‘What does it mean to be an architect? What is the architect’s role and responsibility in society?’” explains Jacobson-Cielecka. She began her career as a journalist, then went on to organize the second Łódź Design Festival with Michal Piernikowski. “The festival sparked the engine of Polish design when it launched in 2007. People met each other, realized they were in the same position, started to talk, exchange experiences,” she recalls. “In the last 10 years, there’s been huge progress.”

Piernikowski also reminisces, “We needed this event in order to wake up.” He enumerates the three original tenets of Polish design: nostalgia, locality and resourcefulness. But that shorthand no longer holds.

Krystian Kowalski’s Mesh chair was launched last year by MDD, Poland’s largest manufacturer of contract furniture. Defined by a halo-like screen of light webbing, it won an iF Award in 2017.

If Italian design is all colourful sensuality, and the Scandinavian aesthetic is minimalist yet full of hygge, what defines Polish design? The prolific Maja Ganszyniec designs collections informed by lived experience and tailored to the needs of millennials. These include a series of high-rimmed glass plates (to make it easier to rest a dish on one’s lap) and a Scandi-inflected suite of wooden ladders as bathroom shelving. Both of these projects were made for Ikea. A skeptic, she doesn’t feel Poland has reached its design tipping point, nor does she subscribe to the notion of Polish design.

“There is no definition yet of such a term,” she explains. “We are still in the process of shaping our identity. I don’t think we know what our uniqueness is, and I would not expect a foreign audience to guess.”

National styles are, in fact, clichés, and woefully inadequate now that social media has erased borders, both geographic and stylistic. In Poland, as elsewhere, designers need only have access to high-end producers to make meaningful work. “We have the best manufacturing at our fingertips,” says Tomek Rygalik. He should know: Two years ago, he founded TRE, a brand offering delightfully geometric accessories with an eye to “simplicity, and a certain rejection of the unnecessary.” He says the line, designed by an international roster, is more of a hit in Asia, but that Poland is emerging as a recognized market. Like Ganszyniec, he also designs for local brands; his Tulli bucket chair for Noti won a Red Dot Award in 2016. But this sophisticated Polish company finds it difficult to compete with European brands that have honed their presence on the world stage for decades. That’s why it’s doubling down on design.

“In the future, we don’t have to limit ourselves to Polish designers,” explains Natalia Sochacka, Noti’s marketing representative. “We believe that the future belongs to inventive initiatives and clever queries.”

One of Rusak’s custom screens (right): a brass structure frames panels of flowers submerged in resin and machined into sections. The flora appear as if fossilized in stone.

One of the most inventive of the new batch of designers is Marcin Rusak. The 30-year-old’s work feels at once fresh and profound. He encases floral blooms in black resin to make chiaroscuro furnishings that recall the art design of Studio Job, but are more restrained. Closer to home, he brings to mind Oskar Zieta, in originality if not in aesthetic. With his idiosyncratic Plopp chair, brought to life with proprietary steel-inflating FIDU technology, Zieta was the first to show how truly great so-called Polish design could be when stripped of its “national” (folk) character. Over the intervening years, Zieta has gone on to build an enviable career, employing over 50 workers and debuting collections annually at Salone del Mobile in Milan.

When I first reached out to Rusak, his assistant thought there’d been a mistake. If he’s based in London, does he still qualify as a Polish designer? “There’s 100 years of flower growers in my family,” the Warsaw native would later tell me. “And they specialized in orchids.” While the family business shut down some time ago, Rusak became fascinated by flowers and is now toying with a new process for submerging them in metal. He settled in the U.K. after studying in Eindhoven and London, but has recently reconnected with Poland.

“I need a manufacturer, and being Polish I’m able to access Polish manufacturers and craftspeople. I’d like to set up a small studio in Warsaw,” he says, “It’s changing a lot. And it’s very vibrant.”

This story was taken from the May 2018 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.