Britain’s hottest architecture collective, Assemble is all about teamwork, public and volunteer collaborations, and making the most of tiny budgets.

Backstory

Heads turned this spring when Assemble was nominated for the Turner Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards, handed out each year by the Tate gallery. It was the first time an architecture practice made the short list. The novelty, however, is one of a string of exceptional facts about Assemble. To begin with, they are all young, in their mid-twenties; and for a start-up they are big, currently made up of 14 co-founders. But it’s their work approach that has triggered the most interest. Hands on, community engaged and locally inspired, their projects stand in stark contrast to the spectator-driven glass and steel boxes that have blanketed London, and other metropolises, in recent years.

How did such an anomaly start? It was with a simple ambition to build. Assemble began in 2010 as a group of mostly architecture graduates keen to work with their hands. Their first project was self-initiated. Using arts grant money of 5,000 pounds, they found a vacant gas station in London and convinced the owner to let them take it over for a short time. “We wanted to make something where people would have a reason to go to,” member Alice Edgerley explains. The result was Cineroleum, a pop-up cinema constructed from cheap industrial materials. Built in three weeks with volunteer labour, it ran for a month and was managed by the team and their friends. It’s an aspect that has become an important trait in Assemble’s projects, where clever management has played an equal role to design.

Cineroleum was a huge hit, and what followed was a series of invitations to design, program and manage similar temporary installations around the city. With Folly for a Flyover (2011), Assemble filled an underpass with a scaffold structure whose gable poked up through a gap between express lanes. The house-like building was clad in wooden bricks hand sawn from reclaimed timber. Together with the Barbican Arts Gallery and local businesses, they programmed and hosted a month of performances, screenings and other activities that brought the space to life. Edgerley explains that the project emboldened the authorities to develop the space further: “There’s now capital investment on the site, with a permanent stage, water and electricity.”

Tipping Point

Despite the team’s successes, Assemble was operating on a voluntary basis. Things changed in 2012 when the London Legacy Development Corporation offered them a deal on a studio space in East London, amid a landscape of derelict industrial buildings awaiting redevelopment. At Sugarhouse Studios, the group explored ways to bring in private creative practices combined with public uses. Acting as property managers, they established a café-pizzeria, and later invited a group of carpenters and a stonemason to inhabit and use the space. They later built Yardhouse, a barn-like structure adorned in multicoloured concrete tiles, to house even more workspaces. Besides creating a rental income, it tested out a strategy that Assemble felt could be applied to the whole neighbourhood. Says Edgerley, “Yardhouse was talking about how affordable workspace could be created, but also about how vacant yards could be turned into assets.”

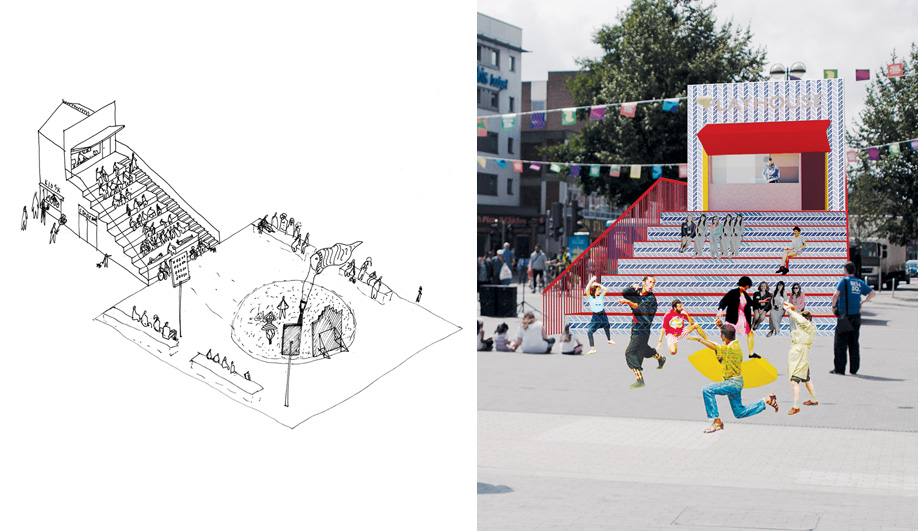

At the same time, Assemble had also been working on temporary interventions and collaborating as projects arose. It was a commission in a suburb of London that gave them the security they needed to become a full-time practice. Design for London commissioned them to redesign a central public square in New Addington. Not satisfied to simply draw out the plans from their new East London digs, they collaborated with locals for nine months to determine ways the space could be activated. They tried pedestrianizing streets, setting up a stage, reorganizing the market and laying down a skate park. The 1:1 scale mock-ups were crucial in understanding the viability of each proposal. More importantly, they engaged local residents and helped to foster a spirit of ownership for the project.

On the books

It was this commitment to community collaboration that earned them the Turner nomination, and what may win them the award when it is announced in December. In Toxteth, a blighted area of Liverpool, a community group had been trying to save some vacant houses from demolition. Through a social investor, Assemble was brought in to create a plan to reinvigorate a cluster of houses and public spaces in the area. The refurbishment, now under way, uses local apprentices and simple, low-cost materials that will instantly lend the street character. Whether efforts like this can be called art is perhaps beside the point. More importantly, it continues Assemble’s mission to find affordable and locally engaged ways to deliver architectural projects.

Their largest project to date is a commission to build an art gallery for Goldsmiths, University of London. Once again, they have turned to found resources to inform the project. In a former Victorian bathhouse, they hope to preserve the more formidable relics, including the massive cast iron water tanks, while providing a proper environment for an art gallery to operate. “It’s about amplifying those pre-existing conditions while creating a range of different spaces to display art,” says Edgerley. Big, small, temporary and permanent, Assemble is amassing a diverse portfolio that demonstrates a common idea: architecture can be co-created, communicative and locally inspired. That’s a big deal in a city where citizens are increasingly alienated from big-money development.

Curriculum Vitae

Location

Stratford, U.K.

Established

2010

Current members

James Binning, Amica Dall, Alice Edgerley, Frances Edgerley, Anthony Engi Meacock, Jane Hall, Joseph Halligan, Lewis Jones, Mathew Leung, Maria Lisogorskaya, Louis Schulz, Giles Smith, Paloma Strelitz and Adam Willis

Awards

2015 Shortlisted for the Turner Prize

Selected projects

Current Goldsmiths Art Gallery, London

Current 10 Houses on Cairns Street, Liverpool

Current Durham Wharf artists’ studio redevelopment, London

2015 The Brutalist Playground exhibition, RIBA, London

2011 Folly for a Flyover, London

2010 Cineroleum, Clerkenwell Road, London